The Gruesome Vegetarian

way, way beyond meat

When I think about the Nobel Prize in Literature, I think of tuxes for men and evening gowns for women. I’m guessing this is what the author wears for the ceremony where the King of Sweden hangs the medal around their neck? I have no idea, as I’ve never actually witnessed a bestowment. Of the writers themselves, I think of those who won in the recent past with whom I am familiar, such as Kazuo Ishiguro (2017, read and watched Remains of the Day), Alice Munro (2013, brilliant short stories, though unfortunately a posthumously terrible person), and Harold Pinter (2005, the tricky Betrayal, plus he adapted Remains of the Day, small world).

Anyway, this is no longer news as it happened a while back, but last year, Han Kang won the storied prize. Not only the first female Asian to do so, but the first from my motherland, South Korea. A ridiculous aside: when I heard that she won, believe it or not, my initial reaction was, “Well, I guess that won’t be me now.” (Hey, delusions of grandeur are underrated!)

She wasn’t supposed to win. According to the odds (shouldn’t be a surprise that people bet on anything nowadays), there were about thirty writers ahead of her, but she nailed the dismount. Good for her, and good for The Land of the Morning Calm! For a tiny little country, South Korea’s culture has been quite dominant lately (Squid Game, K-Pop, Parasite, the latest Hyundai Ioniq sedan, so sleek and pretty). I’ve been meaning to read the book that put Kang on the map, The Vegetarian, for years, and I finally did so.

It’s not what I expected, though I’m not sure exactly what I was expecting. Like the tux and the evening dress, I guess I was thinking along the lines of a stately, calm novel, but The Vegetarian could not be more opposite. It’s been a couple of weeks since I finished it, but I can’t get over just how weird this book is. If I could boil down the story element of this novel into a single sentence, it would be:

Wife stops eating meat, disturbing her husband, intriguing her brother-in-law, and depressing her older sister.

Split into three sections, the first is narrated by the husband of Yeong-hye (the wife, the sudden vegetarian) in the first person, with very short interstitials strewn throughout from her point of view, only to describe her gory dreams. The second section is from the brother-in-law’s POV, told in third person limited, and I found this one to be the strangest of all. Entitled “Mongolian Mark,” it details his obsession with Yeong-hye’s birthmark on her rear. I don’t want to say any more than that because this middle part of the book reads like a fever dream that also happens to be…discomfitingly erotic? Most definitely.

The third and final section is from the long-suffering older sister In-hye’s POV, also narrated in third person limited. (For those unfamiliar with Korean naming traditions, often siblings share either the first syllable of their names or the second. For example, my oldest sister and I both share Sung.) I don’t think I’m spoiling much by saying that our miserable vegetarian does not make a miraculous recovery from all that ails her — this is a thoroughly harrowing book where no one escapes its horrors unscathed.

Adding to the oddness is that the translator of the novel is British, so when I encountered words like mum for mother or lift for elevator, it further dislocated me. There’s an overall formality to the language that just feels off, and yet because so much of what happens in the novel also feels off, two offs make an on, so to speak.

Something that astute readers have pointed out is that the vegetarian herself, outside of the short dream sequences, has no voice in the novel. It’s true, all three sections are told from outside of her point of view, and the logical conclusion one can draw is that this is a metaphor for the lack of female empowerment in patriarchal South Korean culture. I don’t disagree, but my personal feeling is that the bigger reason for her missing voice is that Kang wanted to keep her a cypher. Because we don’t get a sustained section from Yeong-hye, she remains a mysterious figure, and there’s power in that; she becomes a larger-than-life character because we never truly understand her.

The Vegetarian was originally published in 2007, and to me, it seems very much in keeping with other works around this time in South Korea. In fact, according to Wikipedia:

"The idea for the book originally came to me as an image of a woman turning into a plant. I wrote a short story, “The Fruit of My Woman,” in 1997, where a woman literally turns into a plant. After several years (2003–2004) I reworked this image in The Vegetarian, in a darker and fiercer way." [wiki]

Weirdness was in the air in 2003 — Park Chan-wook’s Oldboy and Kim Ki-duk’s Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter... and Spring both premiered that year. How about these two lovely photos to showcase these messed-up movies?

If you aren’t familiar with either of these films, and you don’t mind your brain breaking a little bit, I would recommend screening them. Oldboy is quite bloody at times and overtly disturbing; Summer isn’t so in-your-face, but in some ways it’s even more shocking. It’s been decades since I’ve seen Summer, but I still recall so many images and scenes instantly.

Considering how forgettable so much of what we consume nowadays is, I’m beginning to think that the best metric to gauge the quality of a fictive work is its indelibility. So in that light, The Vegetarian is an unimpeachable success.

If you’ve read The Vegetarian and would like to chime in, please do so in the comments section — I’d love to hear other people’s reactions.

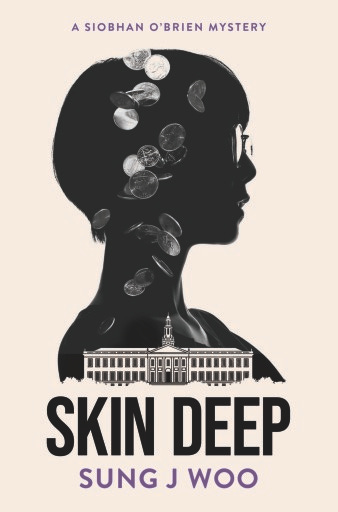

If you made it this far, thank you for reading! In a few months, my two mystery novels will be reissued, and if you haven’t read them yet and want to get an advanced copy, you can query my publisher, Datura. Neither Skin Deep nor Deep Roots are as intense as The Vegetarian, but they do have their moments…feel free to click on the images or the hyperlink in the caption to try to get an ARC.

Yes, this is a strange little book! I enjoyed it, though I did not like or exactly understand the reason for the weird sexual parts, unless it was just to reiterate how so often a woman's body is turned into something sexual? In which case, this just added to that unfortunate truth. And I had forgotten the protagonist never has a voice! She seemed so "voicefull" in the final, sad part, but, hmmm, that was her sister . . .

One of my favorite Korean movies is Okja--have you seen it yet?